Case

A 16 year old female with a history of severe asthma is brought to your community emergency department after a week of respiratory symptoms that have suddenly become much worse. She has been admitted to hospital 4 times this year, including one visit to the ICU. Her respiratory rate is 45 and she is using every accessory muscle she has, but she doesn’t appear to be moving much air. In fact, her lungs are silent to auscultation. She looks tired and the monitor shows her vitals as a heart rate of 140, blood pressure of 99/60, and an oxygen saturation of 88%…

My approach

We all know the ABCs of resuscitation, but A doesn’t always come first. Asthma is a respiratory problem not an airway problem. Unless the patient arrives in arrest, there is no reason to intubate immediately. Adding plastic to the airway only makes things worse.

The immediate action is to start oxygen and bronchodilators. In the severely ill asthmatic I don’t spend too much time debating the finer points of evidence based medicine. Give both albuterol (salbutamol for most countries) and ipratropium bromide. Also, stick to nebulizers in these patients.

-

- Oxygen: Asthmatic patients typically do not require a lot of supplemental oxygen. I apply nasal prongs to everyone, but typically skip the face mask because it is going to be replaced with a nebulizer anyway. Of course, nebulize with oxygen.

-

- Albuterol (and lots of it): You can give 5mg doses repeatedly or run a continuous nebulizer at 10-20mg/hr. It doesn’t really matter, as long as you get as much beta-2 agonist into the lung as possible.

- Ipratropium bromide: 500mcg nebulized every 20 minutes for 3 doses (don’t stop the albuterol nebulizer – mix the two together)

After oxygen and bronchodilators are started, my nurses start hooking the patient to the monitor and place 2 IVs. (This often occurs simultaneously, as we have a large team in resus. However, if you are working with a smaller staff prioritize the breathing meds over the IV.) Essentially all patients with severe asthma are dehydrated and they are also prone to hypotension when switched to positive pressure ventilation. I start a 20ml/kg bolus of my favorite crystalloid as soon as I have IV access.

The definitive treatment of all asthma patients is corticosteroids. EBM nerds will talk forever about oral and parenteral steroids being equivalent, but these patients are all getting their steroids IV. The biggest question is timing. Steroids will take a minimum of 6 hours to have a noticeable effect. Therefore, they are unlikely to help you in the resus room, but the earlier they are given the earlier then are able to work. In the critically ill asthma patient, there may be other therapies to prioritize over a medication that won’t make an immediate difference. Instead of a nurse being tasked with getting steroids, you might need RSI medications, IV fluids, vasopressors, or help setting up non-invasive ventilation. Focus on the therapies that will help this dying patient immediately first, but get a dose of intravenous steroids on board as soon as you have a free minute. Any corticosteroid should be fine, such as methylprednisolone 125mg IV or hydrocortisone 100mg IV.

The final medication that I will routinely include in the management of life threatening asthma is magnesium. That may be a controversial statement and I certainly don’t use magnesium in asthma patients that aren’t actively dying, but there is a modicum of evidence and it seems like the sicker you are the more likely magnesium is to help you. The dose of magnesium sulfate is 2 grams IV repeated up to 3 times in the first hour.

If the patient is not improving with these first line therapies, I consider two second line medications: epinephrine and ketamine.

Epinephrine

Epinephrine has a theoretical advantage for asthmatics who have not quickly responded to beta-2 agonists: it will act as an alpha agonist which may help decrease airway edema as well as providing additional beta-2 agonism. Epinephrine can be safely given to asthmatic patients of any age. (Cydulka 1998 ) Some practitioners will use terbutaline instead of systemic epinephrine, and that is reasonable, but I prefer epinephrine because it is a common medication we are all very comfortable dosing, it adds alpha effects, and I can provide push doses if needed.

Nebulised epinephrine

-

- 0.5ml of 2.25% racemic epinephrine

- 5ml of 1:1000 L-epinephrine

Systemic epinephrine

-

- IM 0.5mg

-

- IV infusion – start at 5mcg/min and titrate to effect

-

- Quick epinephrine drip: 1 mg of epinephrine in a 1L bag of saline. This results in a concentration of 1mcg/mL. Therefore a 60ml/hr infusion will give you 1 mcg/min

- Terbutaline can be used instead (10mcg/kg initial bolus over 10 minutes, then 0.4mcg/kg/min)

Ketamine (+/- Delayed Sequence Intubation)

If the patient is agitated (probably secondary to hypoxia) ketamine is my agent of choice, theoretically as part of a delayed sequence intubation. Ketamine is used to treat the agitation, allow for proper pre-oxygenation of the patient and get the rest of the medications on board. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation can be used as part of this pre-oxygenation. The plan is to use ketamine to pre-oxygenate and buy time to prepare for a safe, controlled intubation. All intubation equipment is at the bedside. However, there are reports of patients improving after the combination of ketamine and BiPAP, obviating the need for intubation.

If the patient is not improving with maximal medical management, it is time to start thinking about positive pressure ventilation and intubation. A common teaching is: when thinking about intubating an asthma patient, wait, and then wait some more, and then continue to wait, but don’t wait too long. If you are considering intubation, BiPAP should almost certainly be tried first. Remember that putting a piece of plastic in the trachea does nothing to help these patients. In fact, it increases airway resistance and dead space. The reason you considering intubation is because of respiratory fatigue and BiPAP can provide exactly the pressure support that these patients need.

How to use NIPPV

-

- Constantly reasses these patients

-

- Have all intubation equipment ready at the bedside

-

- The benefit is all in the pressure support. Start around 8-10mmHg

-

- Set the PEEP very low (1-2), or none at all if your machine will allow

- Most importantly, continue providing beta2 agonists and the full kitchen sink of medical management. NIPPV only allows the patient to temporarily rest their respiratory muscles, it does not solve the underlying asthma pathophysiology

If the NIPPV doesn’t work and you have waited longer than you feel comfortable, it may be time to intubate the patient. In emergency medicine, we love the airway, but asthma is one scenario that we should be wary of grabbing a laryngoscope. Why? Well, in addition to the normal critical care sympathetic tone that we will obliterate with our sedative, these patients are generally hypovolemic and have significant lung hyperinflation limiting venous return that sets them up for hemodynamic collapse. Add to that hypercapnea, acidosis, and hypoxia and it is not hard to understand why the chances of a peri-intubation arrest are so high.

So how should you pass the tube?

There are some reasonable arguments to be made for an awake intubation, however, in this critically ill patient I want to stay within my comfort zone and ensure I am ideally set up for first pass success. Therefore, I use rapid sequence intubation. First, I prepare for post-intubation hypotension. I have a fluid bolus going. Either my nurse has prepared an epinephrine drip (if it wasn’t already running) or I have push dose epinephrine drawn up and ready. I have also pre-set my ventilator so there aren’t any mistakes.

Rapid Sequence Intubation

-

- Nasal cannula on at set at 15L/min for a no desat approach to intubation

-

- Pristine patient positioning

-

- Ketamine 1.5mg/kg

-

- Rocuronium 1.5mg/kg

- Use a large endotracheal tube to facilitate suction and bronchoscopy by our ICU colleagues

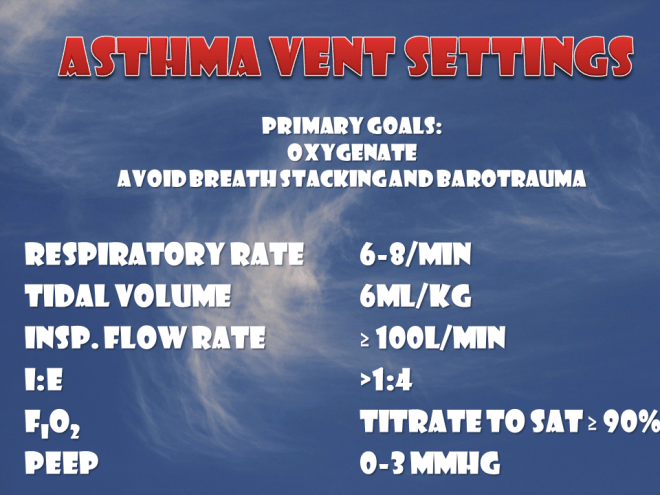

Unfortunately, passing the tube is not the end of your problems, but only the beginning. We often ignore the vent and allow our RTs to be the experts. This is a situation where the wrong vent settings can kill the patient. She is at risk for barotrauma, volutrauma, and hemodynamic compromise from impaired venous return. The ventilator settings are essential.

Ventilator Settings

- The goals are to main oxygenation while minimizing dynamic hyperinflation and barotrauma. They key is to allow as much time as possible to the patient to exhale. Almost always this will require you to accept a degree of hypercapnia

- Set a very low resp rate (6-8/min) to start

-

- Set small tidal volumes (6ml/kg of ideal body weight)

-

- Set inspiratory flow rate ≥ 100L/min

-

- Goal is a long expiratory time (I:E >1:4 ie inspiratory to expiratory ratio of 1:4 or more)

-

- FiO2 100% (but rapidly titrating down to keep sats > 90%)

-

- Minimal or no PEEP (≤5)

-

- The ventilation mode does not matter to me initially because I am going to ensure my patient is paralyzed and sedated. However, be very careful if using assist control mode because if the patient is distressed and starts breathing on their own, they can quickly increase their respiratory rate, limiting their ability to exhale, decreasing the I:E ratio and causing breath stacking.

-

- We are allowing hypercapnia to prevent significant autoPEEP and barotrauma. This can be very distressing, so ensure you are providing excellent sedation

- Goal is a plateau pressure of less than 30mmHg (hold the inspiratory pause button on the ventilator to get the plateau pressure. Or just ask RT). If the plateau pressure is too high, decrease the respiratory rate

Finally, if despite all of the above your patient still looks like she is going to die, there are two rescue options to consider: inhalational agents and ECMO.

Inhalational agents (isoflurane or sevoflurane)

These are very effective bronchodilators. Talk to your anesthesia colleagues. They are usually happy to help.

ECMO

Removing the lungs from the equation while continuing to treat the underlying inflammation and bronchospasm certainly seems to make sense. There are obviously no randomized control trials to support the practice, but there are a number of case reports. It is probably worth getting your local ECMO team on the phone.

Pediatric Dosing

- Albuterol continuous nebulizer: 0.3mg/kg/hr OR:

- 5-10kg: 10mg/hr

- 10-20kg: 15mg/hr

- >20kg: 20mg/hr

- Albuterol intermittent nebulizer: 0.15mg/kg/dose OR:

-

- 2-5 years: 2.5mg/dose

- >5 years: 5mg/dose

-

- Ipratropium bromide

- >20kg: 500mcg/dose

-

- IV fluid bolus: 20ml/kg

-

- Hydrocortisone: 3-5mg/kg

-

- Methylprednisolone: 1-2mg/kg IV

-

- Magnesium sulfate: 50mg/kg repeated up to 3 times in first hour

-

- Epinephrine nebulized:

-

- 0.05 mL per kg (maximal dose: 0.5 mL) of racemic epinephrine 2.25%

- 0.5 mL per kg (maximal dose: 5 mL) of L-epinephrine 1:1,000

-

- Epinephrine nebulized:

-

- Epinephrine IM: 0.01mg/kg (max 0.5mg)

- Epinephrine IV: Start at 0.1-0.5mcg/kg/min

Notes

I was inspired by Salim Rezaie (@srrezaie) of REBEL EM to make some summary images for this post. They certainly aren’t up to Salim’s standards yet – but I will keep trying.

Most asthma deaths are the result of poorly controlled disease that slowly deteriorates over days to weeks. Obviously, the best intervention for these patients would occur long before they arrive in extremis. This is the reason to take all asthma seriously and ensure every patient has follow-up and access to necessary medications.

Although some algorithms include Heliox for status asthmaticus, I have not included it above. There is little evidence to support it. The key problem for patients with life-threatening asthma is that the maximum FiO2 of Heliox is 40%, which may be inadequate. The authors of the Cochrane review conclude: “at this time, heliox treatment does not have a role to play in the initial treatment of patients with acute asthma”, but admit that there may be a role in patients with more severe obstruction, and, as always, note that more study is needed.

IV beta2 agonists: There are two Cochrane reviews, both by Travers (below), that conclude that there is very little evidence to support the use of IV beta2 agonists. Unfortunately, trials generally don’t include the severely ill who are unable to tolerate inhaled beta2 agonist and those are the patients most likely to benefit from an IV route.

Other FOAMed Resources

The Crashing Asthmatic REBELCast

When the patient can’t breathe, and you can’t think: The emergency department life-threatening asthma flowsheet on Emergency Medicine Updates

EMCrit Podcast 15 – the Severe Asthmatic. Ventilator Management for the Asthmatic or COPD Patient, and Delayed Sequence Intubation (DSI) on EMCrit

Asthma…The Music Of The Night and Asthma and the Vent on the PEM ED podcast

Mechanical Ventilation for Severe Asthma on Pediatric EM Morsels

Pediatric Severe Asthma on the SCCM iCritical Care PodCast

A few more with an EBM focus:

The Crashing Asthmatic and The 3MG Trial on Emergency Medicine Ireland

JC: Does Magnesium work in asthma? on St. Emlyn’s

EBM Acute Asthma on Life in the Fastlane

Asthma Medications: where’s the evidence? on EMPEM.org

References

Holley AD, Boots RJ. Review article: management of acute severe and near-fatal asthma. Emerg Med Australas. 2009 Aug;21(4):259-68. PMID:19682010. [Free Full Text]

Stanley D, Tunnicliffe. Management of life-threatening asthma in adults. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain (2008) 8 (3): 95-99. [Free Full Text]

Papiris S, Kotanidou A, Malagari K, Roussos C. Clinical review: severe asthma. Crit Care. 2002;6:(1)30-44. PMID: 11940264 [Free Full Text]

Wener RR, Bel EH. Severe refractory asthma: an update. Eur Respir Rev. 2013 Sep 1;22(129):227-35. PMID: 23997049. [Free Full Text]

Shlamovitz GZ, Hawthorne T. Intravenous ketamine in a dissociating dose as a temporizing measure to avoid mechanical ventilation in adult patient with severe asthma exacerbation. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:(5)492-4. PMID: 18922662

Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:(3)165-75.e1. PMID: 22050948

Weingart SD, Trueger NS, Wong N, Scofi J, Singh N, Rudolph SS. Delayed sequence intubation: a prospective observational study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:(4)349-55. PMID: 25447559

Soroksky A, Stav D, Shpirer I. A pilot prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bilevel positive airway pressure in acute asthmatic attack. Chest. 2003;123:(4)1018-25. PMID: 12684289

Cydulka R, Davison R, Grammer L, Parker M, Mathews J. The use of epinephrine in the treatment of older adult asthmatics. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:(4)322-6. PMID: 3354935

Travers A, Jones AP, Kelly K, Barker SJ, Camargo CA, Rowe BH. Intravenous beta2-agonists for acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2)CD002988. PMID: 11406055

Travers AH, Milan SJ, Jones AP, Camargo CA, Rowe BH. Addition of intravenous beta(2)-agonists to inhaled beta(2)-agonists for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD010179. PMID: 23235685

Rodrigo G, Pollack C, Rodrigo C, Rowe BH. Heliox for nonintubated acute asthma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4)CD002884. PMID: 17054154

Morgenstern, J. Emergency management of severe asthma, First10EM, August 18, 2015. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.661

15 thoughts on “Emergency management of severe asthma”

Great review! Thanks so much for taking the time to write it!

I think you mean inspiratory pause button.

Goal is a plateau pressure of less than 30mmHg (hold the expiratory pause button on the ventilator to get the plateau pressure

Right you are. Thanks for catching that!

This is like sugar for my brain!! I love it!

Excellent review Justin !!

Apart from Cidulka’s review, are there any other bibliographic references on the use of epinephrine in severe asthma?

It has been a while since writing this review, but I don’t remember any other references. The practice predates most of our evidence based medicine, but at one point epinephrine was the standard of care (or so I am told – I was not practicing back then).

Excellent article, I love it. Speaking from experience regarding vent settings – I personally have had 2 status asthmaticus pt’s in the last few years that were extremely difficult to ventilate (2 separate pt’s couple years apart, different facilities). As you noted, I:E should be set with long E time. By the time these pt’s were vented, they were sedated, paralyzed, etc. Despite all that, when placed on the vent, the vent would auto-trigger because the lungs were so hyper-inflated, non-compliant, broncho-contricted… “Normal” vent settings didn’t work, didn’t matter what mode, rate, volume, PEEP up down etc. The first time, the only thing that worked was to do an Inverse Ratio Ventilation for a brief period of time then changing to I:E 1:1 then finally moving closer to 1:3. The second time, same auto-trigger issue. Switched mode, rate, volume, etc… Seemed to get a little better with Pressure Control Ventilation but still wasn’t able to deliver an effective Vt. Changed the I:E to 1:1 then inched closer to 2:1 and success. I’m not a doctor, just an RT of 31 years, but when I couldn’t ventilate a pt, not once, but twice, I did a lot of knob jiggling & changing, trying everything I knew how to do, and when that didn’t work, I tried everything else the vent could do. Just something to file away, it doesn’t seem to get “that bad” often, but it happens.

Thanks for the comment

First: There is no such thing as just an RT. An RT’s expertise is exactly what I want if dealing with this scenario. (I imagine most doctors will feel quite overwhelmed with all the terms you just threw around)

Second: What you describe is why we talk about not intubating in asthma if at all possible. The endotracheal tube does nothing to solve the underlying problems in asthma, but can definitely complicate things tremendously.

Is there are role for high-flow O2 in severe asthma? I had a patient recently with severe COPD/Asthma exacerbation who could not tolerate BPAP, but seem to improve with high flow which they could tolerate better. They were started on it for increasing WOB (RR in the 40s) while still maintaining a normal CO2 and sats around 92% on RA. It seemed to buy us time while the continuous nebs were kicking in…

I think asthma and COPD are very different pathophysiologically, and the answer may be different depending on the cause. There is probably a role in COPD, but I would be much more weary in asthma. I am not aware of any evidence for its use in asthma, and theoretically it could go either way. There is evidence in bronchiolitis, which is a somewhat similar disease pathophysiologically speaking. However, the incredibly high flow rates mean that you won’t be able to nebulize at the same time. I don’t think there is any way that sufficient quantities of nebulized meds make it to the lungs if the patient is simultaneously receiving high flow, and the meds are probably more important? Although it might buy time, asthma patients are usually struggling with ventilation, not oxygenation, so high flow doesn’t really address their needs. Personally, if the patient isn’t tolerating BiPAP and that is the therapy I think they require, I would use ketamine to facilitate the BiPAP rather than switching to high flow. However, there are certainly some patients who are in a grey area, and may not need BIPAP yet. Highflow nasal oxygen is probably more comfortable than facemask oxygen, is probably psychologically calming for the patient, and makes puffers easier to use, so I imagine there are some patients where it could have a role.

Thank you so much for your reply. I need to get more comfy with ketamine sedation in this context, I think.