Case

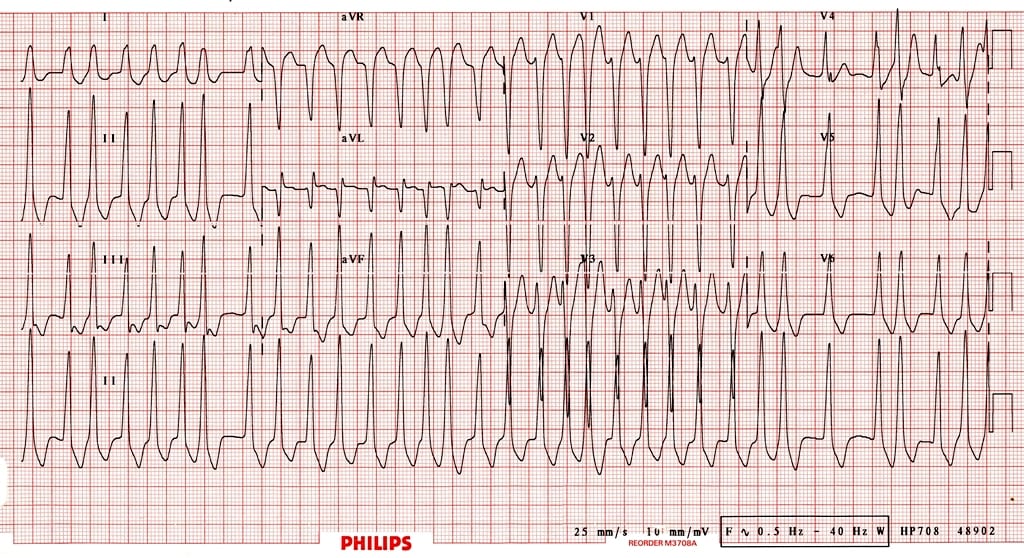

You are finishing up your charts and getting ready to head home for the night. Your relief is currently managing a sick appearing patient in status epilepticus. The charge nurse asks you to see one more patient, who she thinks has SVT, before you head home. You walk into the room and see a grey, diaphoretic man, who you later find out is 67 years old. The chart in your hand says that he has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, but is otherwise healthy. The monitor reveals a heart rate of approximately 205, but it jumps around a lot from beat to beat. His blood pressure is 86/43. He is satting 100%, but is on a nonrebreather. The ECG is narrow complex and irregularly irregular. His wife tells you this all started about 1 hour ago with complaints of dizziness and palpitations but no chest pain. What is your approach to unstable atrial fibrillation?

My approach

Is the atrial fibrillation the cause of the problem or just a symptom?

If the patient’s hypotension and tachycardia are due to sepsis or hemorrhage, controlling the rapid heart rate is not going to help. In fact, the rapid heart rate is probably necessary to maintain an adequate cardiac output. In these situations, the goal should be treating the underlying cause. However, it can be very difficult to determine whether rapid atrial fibrillation is the cause of, or the result of hypotension.

If there is an obvious alternate etiology for the hypotension (hemorrhage, sepsis, etc), I start by treating that. If the atrial fibrillation is long stranding, it is also less likely to be the cause of the instability. Finally, a rule of thumb I have used is that if the rate is less than 150, hypotension is unlikely to be the result of atrial fibrillation, whereas if the rate is greater than 150, the arrhythmia is probably at least a component of the patient’s shock.

If in doubt, make sure to search for alternate causes of shock, even if you decide to treat the atrial fibrillation.

Cardiovert

According to the ACLS guidelines, management is very straight-forward. The patient is unstable, so electrically cardiovert him. Unfortunately, cardioversion never seems to work in these really sick patients. However, I will generally give cardioversion an initial shot.

- Dose: Use full dose electricity on the first attempt (200 joules on my biphasic machine).

- Positioning: An anterior-posterior pad positioning is probably better than anterior-lateral.

- Sedation: Sure, a little pain is better than death. On the other hand, although your patients may not appreciate how sick they really are, they will certainly remember any pain you inflict. Some sedation and analgesia will be greatly appreciated. The choice of agent is difficult. Essentially all sedatives will drop your blood pressure, which could be catastrophic. Ketamine, my go to in many other scenarios, has a prolonged sedative effect, which is problematic when I am trying to assess ongoing shock and mental status. Therefore, etomidate is my first line agent for this patient, at a dose of 0.1mg/kg or approximately 7-10mg. A subdissociative dose of ketamine or a small dose of fentanyl may also be reasonable.

- I will usually try 2 or 3 shocks in rapid sequence, but if the first is not successful, I have rarely seen success on a second or third.

- Anticoagulation: If the onset of atrial fibrillation is unknown, or the patient is in permanent atrial fibrillation, the risk of stroke after cardioversion is increased. In the unstable patient, a rapid attempt at cardioversion is still warranted, but starting heparin as soon as possible afterwards is a good idea.

Unfortunately, cardioversion rarely works in truly unstable atrial fibrillation. At this point, the key question is:

Is this WPW (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome)?

The main feature I watch for is bizarre appearing QRS complexes that change in width from beat to beat. Also, atrial fibrillation with a rate greater than 220-250 is not compatible with AV node conduction, but rather an accessory pathway.

If WPW, do not start any medications that could slow conduction through the AV node (amiodarone, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers). This could paradoxically increase the rate of conduction through the accessory pathway, leading to ventricular rates of >300, which is also known as ventricular fibrillation. In the setting of WPW, electrical cardioversion is your best choice – and luckily, this is a subset a patients for whom electricity is likely to work. The only other safe option is probably procainamide (17mg/kg slow IV bolus).

For all other patients, the next step is to manage the hypotension:

Definitive therapy of hypotension requires correction of the arrhythmia. However, the patient is in shock and rate control agents will worsen hypotension.

Management of hypotension almost always start with some fluids. With rapid atrial fibrillation resulting in cardiogenic shock, you have to be very careful of causing pulmonary edema. Also, there little reason to believe that this patient is significantly fluid depleted. However, the rate control agents are all vasodilatory, and therefore some fluid resuscitation may be helpful. I generally hang a small (500ml) normal saline bolus and reassess frequently.

The primary temporizing treatment of this patient’s hypotension will be a vasopressor. In general, I prefer controlled drips of pressors when I have the option. In this scenario, I want vasoconstriction with limited impact on heart rate (chronotropy). My go to agent would be norepinephrine, started at 5mcg/min and titrated to a diastolic blood pressure of 60.

However, we all know that starting drips in emergent situations can take much too long. In practice, my go to vasopressor is often going to be push dose phenylephrine:

- Draw up 1ml of phenylephrine (10mg/ml) into a syringe.

- Inject the entire 1ml (or 10mg) into a 100ml bag of normal saline.

- You now have 10mg in a total of 100ml, or 100mcg/ml.

- Inject 0.5-2ml (50-200mcg) every 1-5minutes, as needed.

- Goal of diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 60.

Don’t just read about it, watch Dr. Scott Weingart show you how to mix push dose phenylephrine:

Once the blood pressure is temporized, it’s time to start the real treatment of this patient’s shock: getting control of the heart rate. The two options I would consider are diltiazem and amiodarone. (Some people would consider beta-blockers here, but I think there is ample evidence that calcium channel blockers are more effective at rapidly achieving rate control, which is exactly what I want here.) I actually don’t think there is much of a difference between amiodarone and diltiazem, but the cardiologists I work with always seem to prefer amiodarone. Personally, I think diltiazem does a better job of rapidly achieving rate control.

Amiodarone

- 150mg IV bolus (slow IV push, or infused over 10 minutes), then 1mg/min IV infusion (for the first 6 hours – so hopefully someone has taken over by then)

Diltiazem

- I give this is one of two ways:

- Diltiazem 25 mg in a minibag and slowly dripped in over about 10-15 minutes.

- Diltiazem 5-10mg (small doses) pushed by me every 1-2 minutes.

- After an appropriate heart rate is reached (for these very sick patients I am generally happy to get them to less than 130), I switch to either the conventional diltiazem drip at 5-15mg/hr or 30-60mg of PO diltiazem.

- There may be some value to giving IV calcium (1 or 2 grams of calcium gluconate) before starting the diltiazem to reduce the hypotensive effects of the medication.

The atrial fibrillation still isn’t controlled – what now?

The good news is that unlike electrical cardioversion, rate control with diltiazem is almost always effective. If the heart rate has come down, but the blood pressure has not improved, it is time to restart the search for other possible causes of shock.

If the patient remains unstable and you have not been able to control the heart rate, it is time to rapidly involve the expertise of a cardiologist. While waiting for them to arrive, I would consider adding magnesium or digoxin.

Magnesium

- 2-4 grams IV over 10-15 minutes.

- Has been shown to modestly decrease heart rate and also possible increase the rate of spontaneous reversion to sinus rhythm.

Digoxin

- 500mcg IV over 20 minutes.

- Generally takes to long to be really useful in an unstable patient.

Notes

Despite unstable atrial fibrillation being a relatively common problem, information on its management seems (at least based on my review) to be very sparse. Almost every textbook and guideline that I found just states that you should follow the ACLS protocol and electrically cardiovert patients that are unstable. I could not find a single textbook that explored what to do when cardioversion does not work, which seems to be the majority of the time. Understandably, there are also no clinical trials that cover these very sick patients. Therefore, most of the above it based on collated expert opinion and common sense. I cannot support this approach with evidence, but I don’t think that there is any evidence based approach to the dying rapid atrial fibrillation patient.

The most common alternate management strategy I have encountered focuses on just using fluid boluses to support the pressure while loading amiodarone. There is no evidence that vasopressors help patients, so I can’t argue, but I have a hard time not temporarily making the numbers better while I wait for rate control to occur. Maybe I am treating my own anxiety more than the patient?

Click here for more emergency medicine and critical care resuscitation plans.

Other FOAMed Resources

EMCrit Podcast 20 – The Crashing Atrial Fibrillation Patient

Calcium before Diltiazem may reduce hypotension in rapid atrial dysrhythmias and Atrial Fibrillation Rate Control in the ED: Calcium Channel Blockers or Beta Blockers? on ALiEM

Approach to shocky patient in AF w/ RVR and Magnesium infusions for atrial fibrillation and torsade on PulmCrit/EMCrit

A-Fib Unleashed! and Atrial flutter, fibrillation and ablation on ERCast

Episode 20: Atrial Fibrillation, Best Case Ever 7: Atrial Fibrillation, and Episode 57: The Stiell Sessions 2 – Update in Atrial Fibrillation 2014 on Emergency Medicine Cases

Fast atrial fibrillation on EM Tutorials

SGEM#133: Just Beat It (Atrial Fibrillation) with Diltiazem or Metoprolol? and SGEM#88: Shock Through the Heart (Ottawa Aggressive Atrial Fibrillation Protocol) on The Skeptics Guide to EM

References

Bontempo LJ, Goralnick E. Atrial fibrillation. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 29(4):747-58, vi. 2011. PMID: 22040705

Goralnick E, Bontempo LJ. Atrial Fibrillation. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 33(3):597-612. 2015. PMID: 26226868

Piktel JS. Chapter 22. Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances. In: Tintinalli JE et al eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=348&Sectionid=40381483

Yealy DM and Kosowsky JM. Chapter 79. Dysrhythmias. In: Marx JA et al. eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8e. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

Onalan O, Crystal E, Daoulah A, Lau C, Crystal A, Lashevsky I. Meta-analysis of magnesium therapy for the acute management of rapid atrial fibrillation. The American journal of cardiology. 99(12):1726-32. 2007. PMID: 17560883

Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Loh P. Anterior-posterior versus anterior-lateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 360(9342):1275-9. 2002. PMID: 12414201

Verma A, Cairns JA, Mitchell LB. 2014 focused update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 30(10):1114-30. 2014. PMID: 25262857

Scheuermeyer FX, Pourvali R, Rowe BH, et al. Emergency Department Patients With Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter and an Acute Underlying Medical Illness May Not Benefit From Attempts to Control Rate or Rhythm. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:(5)511-522.e2. PMID: 25441768

Photo by Alexandru Acea on Unsplash

Morgenstern, J. Unstable atrial fibrillation – ED management, First10EM, December 7, 2015. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.1027

15 thoughts on “Unstable atrial fibrillation – ED management”

Excellent article. I would like make a couple of points.

Atrial fibrillation that is associated with hemodynamic compromise has a success rate for primary cardioversion of less than 20% in one study. As pointed out, success rate may be increased by the use of biphasic energy (with an energy level of 200 joules). If the patient is stable enough, prior correction of hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia also increases success of cardioversion.

If cardioversion is unsuccessful, it may be tried again following intravenous amiodarone (a bolus dose of 5 mg/kg over 30 minutes or an infusion of 2 mg/min for 4 hours). Amiodarone provides acute control of heart rate through its β-blocker actions and may itself result in pharmacologic cardioversion. Following successful cardioversion, an infusion of amiodarone (1 mg/min) should be administered until the patient is able to take oral amiodarone or a β blocker.

Intravenous sotalol or ibutilide may be used as an alternative in patients with good left ventricular function. If, despite these measures, atrial fibrillation persists, pharmacologic control of heart rate may be achieved by an intravenous β blocker, diltiazem or digoxin as described in the article. As mentioned, intravenous digoxin may be tried, but it has limited efficacy in the setting of heightened adrenergic tone.

Thank you for the excellent comment

Excellent point about electrolyte management – I never have that info available during the initial resuscitation in the ED, but important not to forget to address as the resus progresses.

For afib with WPW also should avoid adenosine and digitalis. I think of ABCD with this rhythm.

A-adenosine, amiodarone

B-beta blockers

C-calcium blockers

D-digitalis

Procainamide is safe if hemodynamically stable.

Thank you for your time and effort , moreover , I would like to know about the using of Amiodarone in atrial fibrillation and WPW ,because it is working on both the AV node and on the accessory pathway .

Thank you.

There are a number of case reports of bad outcomes after using amiodarone in WPW. A good summary can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17355684

Very nice comprehensive detailed approach,

Thanks

I wish there was a note about anticoagulation approach..

With regards

Thanks for the comment. I didn’t get into the anticoagulation approach, because I don’t think it matters much in the acute management. It is also a complex topic, with some skewed and biased evidence. For the most part, I think it warrants a conversation with your primary care provider, because it is a big decision. Personally, I would probably use coumadin, or at least try it to see if I had relatively stable INRs.

Wanted to ask – why not verapamil? Diltiazem is less cardio selective and can give hypotension. All books recommended Diltiazem but doesn’t state why.

A week ago had pt who had AFib for 3days (most likely) but today came in with atrial flutter 150x, BP 90/60, all in cold sweat. Tried verapamil with goal to slow conduction. Dropped BP to 54/20, became unresponsive. While we’re charging defibrillator, she cardioverted spontaneously to AF with normal BP.

Cardiologist scolded me for the choice of medication, but when asked, could not state a better approach. So… Was there? (She was discharged day after, no significant heart disease)

Thanks for the comment.

I have never seen any convincing evidence that there is any real difference between verapamil and diltiazem. My suggestion would be to use whatever you are comfortable with.

In your case, treating hypotension with either phenylephrine or norepinephrine, as mentioned in the post, and potentially pretreating with calcium before using a calcium channel blocker might help prevent the hypotension. However, in hypotensive patients (even if you think they are otherwise stable) my first move would be to electrically cardiovert.

wanted to know your approach for a patient presenting with Acute Rapid AF and Hypotension but in and out of AF…… would electrical cardioversion help along with Amiodarone.

Depends a lot on the patient presentation, but in and out of AFib makes it sound like that is not the cause of the hypotension. I would treat the underlying cause and ignore the AFib. If you think the AFib is the primary cause, medical management makes more sense than electrical cardioversion, as they are likely to revert. You could use amiodarine or just rate control supported by pressors.

Thank you. Logically right. Thats what we did.

This is a great practical approach to atrial fibrillation. This is also my practice in intensive care. I appreciate your emphasis on atrial fibrillation as a “symptom” rather than a cause. I have seen many cases where there is obviously an underlying pathology driving the AF (usually unrecognised sepsis), but the clinicians are cognitively anchored on managing the AF (which won’t get better unless the underlying driver is treated). Good job.