Everyone knows about the CRASH-2 trial. It is now a decade old. It doesn’t seem like it desperately needs a new blog post, but I think that understanding this trial is important when trying to interpret the results of the newer CRASH-3 or WOMAN trials, and other TXA research that is on the horizon. So let’s review CRASH-2.

The paper

CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2010; 376(9734):23-32. PMID: 20554319 Clinicaltrial.gov NCT00375258

The Methods

This is a pragmatic, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Patients

Adult trauma patients with significant hemorrhage (defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 90 and/or a heart rate greater than 110), or who were at risk or significant hemorrhage, and who were within 8 hours of their injury.

- Doctors had to be “substantially uncertain” about whether or not to give TXA. They don’t tell us how many patients were excluded by this criterion, but it could introduce significant selection bias.

Intervention

Tranexamic acid: 1 gram IV over 10 minutes and then 1 gram IV over 8 hours.

Comparison

Placebo.

Outcome

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality by 28 days.

The Results

They enrolled 20,211 patients. They lost incredibly few patients for a trial this size (less than 1%). Almost all patients got the loading dose (99.1%), but about 6% did not receive the full 8 hour infusion.

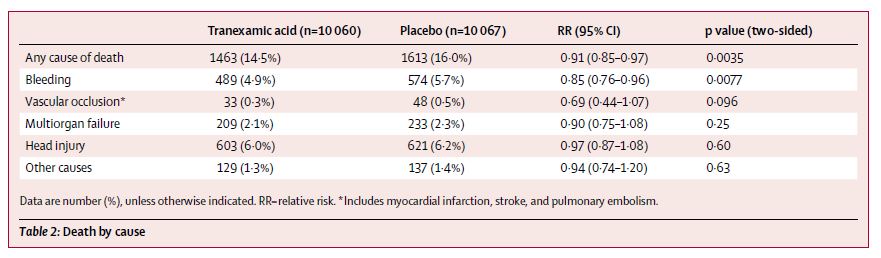

All cause mortality was reduced with TXA (14.5% vs 16.0%; RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.85-0.97; p=0.0035). This translates to a NNT of 67 to save 1 life over 28 days. Death due to bleeding was also reduced (4.9% vs 5.7%, p=0.007).

There was no difference in the number of patients requiring a blood transfusion (50.4% vs 51.3%, p=0.21). There was no difference in the mean total blood cells transfused (6.1 vs 6.3 units). There was no difference in the need for surgical interventions (47.9% vs 48.0%).

They also looked at the percentage of patients who were “dead or dependant” at discharge or 28 days, and there was no difference (34.3% vs 35.4%; RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.93-1.00; p=0.12).

There was no difference in vascular occlusive events (1.7% vs 2.0%).

My thoughts

This is a huge and very important trial. It did a lot of things very well. There was very little loss to follow up. There were very few protocol violations. Blinding was done properly. We should wish that every trial had methodology of this quality.

However, no trial is perfect and no single trial can define scientific truth. There are a number of issues that need to be considered when we try to decide whether we think that results of CRASH-2 would be seen again if the trial was replicated, and also whether the results apply to our own patients.

Some of the standard concerns apply. Selection bias could be a big concern. Physicians were allowed to exclude patients if they thought that TXA was either indicated or contraindicated, but they don’t tell us how many patients were excluded in this way. It doesn’t really make sense to me as an exclusion criteria, seeing as this was the first real trial of TXA in trauma, so I am not sure how any doctor could have known who needed or didn’t need to be treated.

I also think that it is interesting to consider the biologic plausibility of the results we are seeing. There is some evidence that TXA decreases bleeding in surgery, and we know that coagulopathy is a big issue in trauma, so TXA makes sense. (Henry 2011) However, there was no change in the number of patients needing transfusions, the total amount of blood transfused, nor the total number of patients requiring interventions in CRASH-2. If there was no change in bleeding, it isn’t clear how an agent that stops bleeding could have possibly decreased mortality. (To be fair, the total amount of blood might have been balanced out by survivorship bias. However, if that was the case you would expect the proportion of patients transfused to have changed, and it didn’t.)

There are also concerns about the external validity of the results. A strength of this study is that it included patients from a large number of different health care systems around the world, but it is also a potential weakness. The trauma systems included vary wildly, and a drug that decreases bleeding might be more or less valuable in places with immediate access of trauma surgeons and interventional radiology, as compared to the sites that didn’t even have access to a phone line for randomization. Although the details aren’t described in the manuscript, it has been reported that “fewer than 2% of the patients in CRASH-2 were treated in countries that routinely provide rapid access to blood products, damage-control surgery and angiography, and advanced critical care.” (Gruen 2013) That being said, they have done a subgroup analysis, and there doesn’t seem to be a difference in the results based on the continent. (Roberts 2013) Furthermore, although we aren’t provided with injury severity scores, some have argued that the mortality was higher than expected in the CRASH 2 placebo group, considering what we know about these patients. (Gruen 2013)

I often talk about trials that have very low fragility indexes. In fact, it comes up so often that people might assume that every trial has a tiny fragility index, but they don’t. The fragility index for CRASH 2 is 48. That is a reassuring number. However, despite the very small percentage of patients lost to follow-up, CRASH-2 is a massive trial. A total of 84 patients were lost. Depending on their outcomes, those lost patients would be enough to change the results of the trial.

I find it really interesting that there was no difference in the number of patients with a bad outcome, as defined as “dead and dependant”. Considering the benefit in terms of all cause mortality, this seems to indicate that the extra survivors in the TXA group might have had bad neurologic outcomes. We always talk about neurologically intact survival as being the most important outcome, but I have never really heard it talked about for CRASH 2. Looking through their numbers, I don’t see a big increase in bad neuro outcomes, but the fact that there is no difference in “death and dependency” is interesting.

On the other hand, there is a chance that CRASH-2 underestimates the benefit of TXA. Death due to bleeding only occurred in about 5% of the population, and this is the only disease specific mortality that TXA reduced. Also, the biggest effect was seen in the sickest patients (there was a 4.5% absolute reduction in mortality among those patients presenting with a systolic blood pressure of less than 75.) Despite trying to enroll high-risk bleeding trauma patients, only half of this cohort required a blood transfusion. It is possible we would have seen better results in a sicker cohort of patients.

CRASH-2 does not report an increase in adverse events, and that finding has been repeated in subsequent trials, but it seems hard to believe when looking at any agent that alters the coagulation cascade. They didn’t have a system to look for thromboembolism in CRASH-2. These harms can occur in a delayed fashion, and considering that many patients were enrolled at hospitals that didn’t have a phone line for randomization, there is reason to think that harms might have been missed. Others have also raised concerns about the possibility that harms were missed in CRASH-2. (Gruen 2013) In comparison, thrombotic complications were increased almost 10 fold in the MATTERS trial, although MATTERS was not a randomized trial. (Morrison 2012)

The use of in-hospital mortality could also introduce some bias. It is very likely to catch all traumatic causes of death, but it might miss patients who died of complications from the study drug. For example, it is easy to imagine a patient who was well enough to be discharged after their trauma, but who subsequently died of a massive PE. That patient wouldn’t be captured in the primary outcome. In other words, the use of in-hospital mortality is likely to accurately represent the expected benefit, but might under-estimate the harms.

As a side note, these authors specifically list their use of all cause mortality as a strength of this study, which is interesting considering the emphasis on the much less accurate and less meaningful disease specific mortality in CRASH 3 and WOMAN.

It is important to remember that a single trial never gives us all the details required. There are too many ways that a single trial can be wrong due to bias or chance alone. Furthermore, after just one trial, we cannot know which patients truly need an intervention. Although people talk about TXA as the standard of care after CRASH 2, many experts have recognized the need for further research, and there are ongoing RCTs, like the PATCH-Trauma study. (Gruen 2013, Napolitano 2013; Pusateri 2013) It is reassuring that the same mortality benefit was seen in the MATTERS trial, although the retrospective observational nature the data makes bias a problem. (Morrison 2012) On the other hand, one large observational trial in a civilian trauma population demonstrated no mortality benefit (despite being widely reported as positive). (Cole 2015)

CRASH-2 was compelling enough that I prescribe TXA to all my trauma patients with significant hemorrhage, but I am also keenly aware of the fact that the results may not hold up to replication, or may not apply within my trauma system. An RCT within a North American trauma system would be welcomed.

Bottom line

CRASH 2 demonstrated a 1.5% absolute reduction in mortality among trauma patients who were bleeding or at risk of bleeding. Although it is an excellent trial, it is not sacrosanct, and it’s various shortcomings need to be considered.

Other FOAMed

Tranexamic Acid (TXA), Crash 2, & Pragmatism with Tim Coats – EMCrit

How CRASH-2 got it wrong – Maryland CC Project

References

Cole E, Davenport R, Willett K, Brohi K. Tranexamic acid use in severely injured civilian patients and the effects on outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Annals of surgery. 2015; 261(2):390-4. [pubmed]

CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2010; 376(9734):23-32. PMID: 20554319

Gruen RL, Jacobs IG, Reade MC. Trauma and tranexamic acid Medical Journal of Australia. 2013; 199(5):310-311.

Henry DA, Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. In: . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Chichester, UK. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 1996.

Morrison JJ, Dubose JJ, Rasmussen TE, Midwinter MJ. Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012; 147(2):113-9. [pubmed]

Napolitano LM, Cohen MJ, Cotton BA, et al. Tranexamic acid in trauma: how should we use it? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 74: 1575-1586.

Pusateri AE, Weiskopf RB, Bebarta V, et al. Tranexamic acid and trauma: current status and knowledge gaps with recommended research priorities. Shock 2013; 39: 121-126.

Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats T, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2013 Mar. (Health Technology Assessment, No. 17.10.) Chapter 6, Discussion. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK260385/

Morgenstern, J. The CRASH-2 trial (a review), First10EM, February 17, 2020. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.10920

3 thoughts on “The CRASH-2 trial (a review)”