It’s time for another edition of the research round up and BroomeDocs journal club – a collection of the most interesting emergency medicine research I have encountered in the last few months. This time around we have (of course) CRASH 3, some articles on laceration repair, improving the ED experience for pediatric patients, CT in syncope, and a great deal more…

CRASH 3 – A world where no change in mortality transforms into 10s of thousands of lives saved

The CRASH-3 Trial Collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019; PMID: 31623894 [free full text]

This is a massive RCT comparing TXA to placebo in 12,000 patients with isolated head trauma. There was no difference in the primary outcome. There was no difference in mortality. There was no difference in disability. In other words, it was a convincingly negative trial. That being said, people have been really excited about the results, and many people are even calling for guidelines to start recommending TXA. There is even a video released by the researchers claiming TXA is going to save tens of thousands of lives. (Remember the part above where I said morality was unchanged?) This excitement is based off a subgroup (patients with GCS above 8) that was statistically positive, but the problem is that it was a statistical change in an unreliable and non-patient oriented outcome – disease specific mortality. If all cause mortality is unchanged, patients don’t care much what we write on their death certificates, and neither should we.

Bottom line: Based on this trial as it is published, I see no role for TXA in isolated head trauma. (See the main post for some important caveats.) Given that this is the third massive trial of TXA in a row with negative results, I think we might want to revisit the CRASH2 trial.

You can read more about CRASH3 and why disease specific mortality is a bad outcome here.

Slow but steady wins the race

Watanabe BL, Patterson GS, Kempema JM, Magallanes O, Brown LH. Is Use of Warning Lights and Sirens Associated With Increased Risk of Ambulance Crashes? A Contemporary Analysis Using National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) Data. Annals of emergency medicine. 2019; 74(1):101-109. PMID: 30648537

This study looks at a huge database of more than 20 million EMS activations. The authors compare the rate of accidents that occured while ambulances were driving “lights and sirens” to the rate when they were driving without. Overall, they identify 2,539 crashes, which is 12 for every 100,000 ambulance runs. There are more crashes when driving with lights and sirens. The exact numbers are a little unclear to me, because the numbers are different in the text and tables, but there is a small increase while the ambulance is driving to the patient (OR 1.2) and a bigger increase while transporting to the hospital (OR 2.4). The absolute numbers are very small. This is retrospective, observational data, so it is possible the difference isn’t real. (Maybe you turn on the lights and sirens more often at high traffic times, or on longer drives, which would also increase the incidence of crashes. However, the incidence was the same morning, afternoon, and night, as well as in urban and rural areas.) The big question is, given the potential increase in risk, are lights and sirens worth it? Prior research has shown that lights and sirens only save a few minutes, at best. There are only a handful of scenarios where a few minutes makes a difference in patient outcomes. Based on this data, ambulances are driving to the patient with lights and sirens about 75% of the time, and to the hospital about 25% of the time. Maybe that is too much?

Bottom line: If you are a paramedic reading this, or you advise EMS, think carefully about when lights and sirens are necessary.

Close only matters in horseshoes, hand grenades, and laceration repair

Esmailian M, Azizkhani R, Jangjoo A, Nasr M, Nemati S. Comparison of Wound Tape and Suture Wounds on Traumatic Wounds’ Scar. Advanced biomedical research. 2018; 7:49. PMID: 29657934 [free full text]

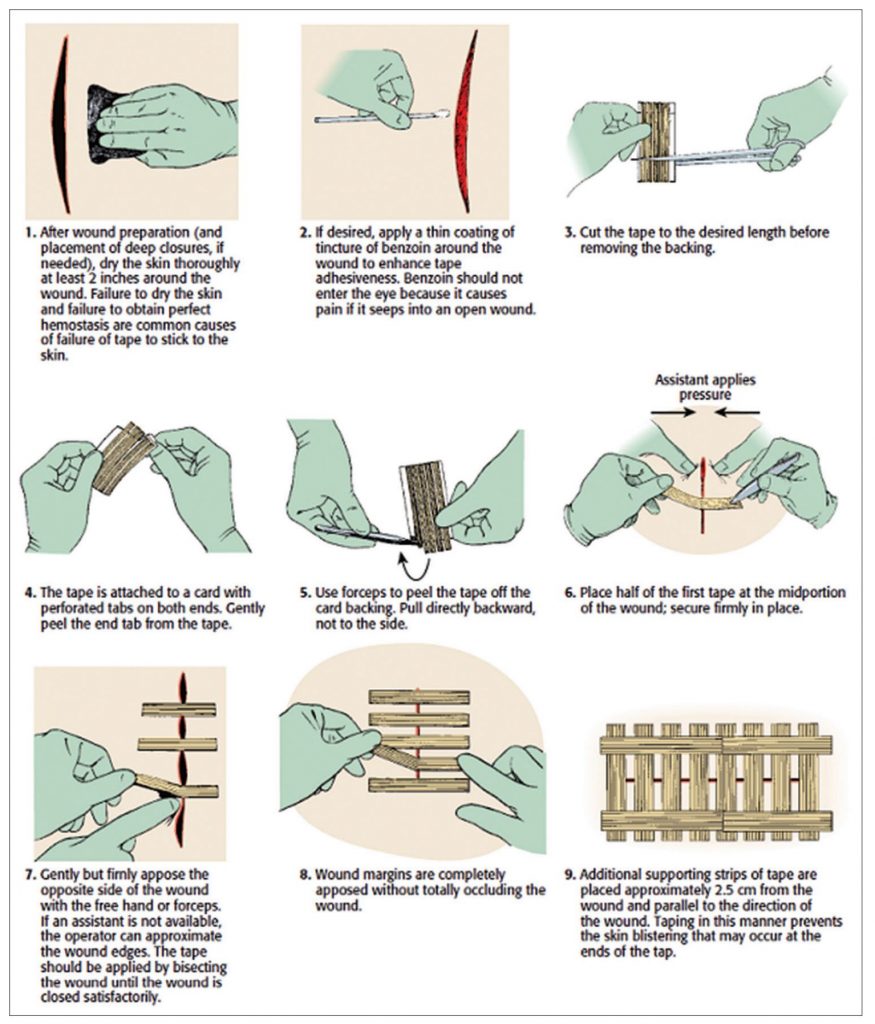

Some people get really picky about laceration repair. So far, all the literature I have encountered convinces me that as long as you can prevent infection and the wound edges are close, the technique you use is probably irrelevant. (Hence the rapid rise in skin adhesives). This is an RCT comparing sutures to tape in lacerations less than 5 cm long, less than 5 mm deep, not involving muscle, and not requiring debridement. All wounds were irrigated. The suture group got 0.6 nylon stitches every 5 mm. (That seems way too close together, as I will touch on next). The other group was taped (using steristrips). They were very particular about their tape technique, first swabbing the skin with benzoin tincture, then taping across the wound, and then adding another 2 pieces of tape on either side of the wound parallel to the laceration to reinforce the repair. They randomized 90 patients and lost 8. At 2 months, the scar width was the same in both two groups (2.9 mm with sutures and 2.5 mm with tape, p=0.07). In the subgroup with wounds less than 20 mm, the tape group was statistically better (1.7 vs 2.5 mm, p=0.01). Over all the results aren’t that impressive, and it is a small, single centre trial, but it fits with most other laceration repair literature I have seen. As long as you get the edges next to each other, the technique probably doesn’t matter.

Bottom line: Steri-strips and sutures were equivalent here. As long as the edges come together, I doubt it matters what technique you used.

But the sutures themselves don’t need to be close

Sklar LR, Pourang A, Armstrong AW, Dhaliwal SK, Sivamani RK, Eisen DB. Comparison of Running Cutaneous Suture Spacing During Linear Wound Closures and the Effect on Wound Cosmesis of the Face and Neck: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA dermatology. 2019; 155(3):321-326. PMID: 30649154

This is another laceration study, this time looking at how far apart we should put our sutures. The study may not be all that relevant to the ED because these are patients with a surgical wound post Mohs microsurgery, meaning that they are elderly skin cancer patients and they all had subcuticular sutures placed before the skin was closed. For the skin sutures, each patient had their wound divided in half. One side was closed with sutures every 2 mm and the other side had sutures every 5 mm. Based on a validated scar score, there was no difference between the groups at 3 months based on blinded assessments. My big problem with this study is that I think even 5 mm is still way too close. I am constantly telling my students they put in way too many sutures. I generally continuously bisect the wound, placing as many sutures as required to keep the wound edges approximated under light tension. I think the closest my sutures ever get is about 1 cm apart. So I would like to see this study repeated with a more sensical spacing, but I think the message is right: you can space your sutures out.

Bottom line: Sutures don’t need to be jammed right next to each other. Just place enough to keep the edges approximated.

“They do not care how much you know until they know how much you care”

Graham B, Endacott R, Smith JE, Latour JM. ‘They do not care how much you know until they know how much you care’: a qualitative meta-synthesis of patient experience in the emergency department. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2019; 36(6):355-363. PMID: 31003992

This is a qualitative meta-synthesis that reviews the literature looking at patient experience in the emergency department. It is hard to summarize in just a single paragraph. For a better summary, you can read this blog post, or just read the paper. One major theme was that patients require good communication to develop an interpersonal relationship, to help alleviate anxiety, and to receive important information. Patients also have emotional needs, summarized in three main groups: coping with uncertainty, recognition of suffering, and empowerment. Obviously, there are specific needs when it comes to the care received. Waiting is a big component of patient experience, and we shouldn’t be surprised that our patients find waiting rooms uncomfortable, crowded, lacking in privacy, and lacking appropriate infection control measures. Finally, emergency departments frequently fail to address basic human needs, such as water, toilets, privacy, or a comfortable place to sit.

Bottom line: We could all do better in considering the patient experience, both in our day to day work, and as we try to redesign emergency departments to be better places.

Classic modern medicine: Order 800 CTs, find nothing

İdil H, Kılıc TY. Diagnostic yield of neuroimaging in syncope patients without high-risk symptoms indicating neurological syncope. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019; 37(2):228-230. PMID: 29802003

I really hope we all already know this: syncope does not require a head CT. This is a retrospective look at 1114 syncope patients with no or mild head trauma (GCS 14 or 15), excluding patients with focal neurologic findings, confusion, severe headache, or on anticoagulation. (Only 79 patients out of 1193 screened were excluded, so it is most syncope patients.) I am not sure why, but a huge number received neuroimaging: 62% CT head and 10% MRI. (When I saw that 2/3rds of the patients were scanned, I was all ready to make fun of our American colleagues for their rampant overtesting, but this paper is actually from Turkey.) Not a single one of these scans revealed a clinically important finding. These patients were found retrospectively, so it is possible that patients with positive imaging were coded as something other than syncope. Also, there was no standard follow up for the group of patients who didn’t get imaging. However, we know that, unless it is accompanied by a thunderclap headache or major head trauma, there is essentially no role for neuroimaging in syncope patients.

Bottom line: 0 out of 808 is not an impressive stat. Syncope doesn’t generally need a head CT.

Orthostatic vitals don’t help

White JL, Hollander JE, Chang AM, et al. Orthostatic vital signs do not predict 30 day serious outcomes in older emergency department patients with syncope: A multicenter observational study. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019; PMID: 30928476

Another syncope paper, this time an observational study looking at 1974 elderly (over 60) patients with syncope to see if orthostatic vital signs predicted bad outcomes. They didn’t. They used a really long list of adverse events. About 15% of the population had an adverse event within 30 days, but it was the same whether or not you had abnormal orthostatic vital signs in the ED. There are a few problems with this paper, so in isolation it can’t prove that orthostatic vital signs are useless, but it fits perfectly with all the other research out there, which makes me pretty comfortable in concluding that orthostatic vital signs are useless.

Bottom line: This study demonstrates that routine use of orthostatic vital signs in an elderly population is not helpful at identifying patients at high risk for adverse events.

I love my job, but some parts suck

Vukovic AA, Poole MD, Hoehn EF, Caldwell AK, Schondelmeyer AC. Things Are Not Always What They Seem: Two Cases of Child Maltreatment Presenting With Common Pediatric Chief Complaints. Pediatric emergency care. 2019; 35(6):e107-e109. PMID: 30489490

This is a disturbing paper. I include it because I hated reading it and hated thinking about it. As much as we all recognize our role in identifying child abuse, I think the natural human state is denial – a cognitive defense against the horrors of reality. I know I could have (and probably would have) missed abuse in both of the presentations described. Case 1 was conjunctivitis in an 8 year old girl that turned out to be gonorrhea. Case 2 was a 2 year old girl admitted to hospital with vomiting, fever, and lethargy from what was thought to be gastroenteritis, but ultimately turned out to be a traumatic bladder rupture. I include the paper to remind us that we need to fight that denial and remain vigilant. As hard as it is for us to consider these horrid acts, it is infinitely hard for the children who experience them. It is our job to protect them.

Don’t be a Jedward

Fogarty E, Dunning E, Koe S, Bolger T, Martin C. The ‘Jedward’ versus the ‘Mohawk’: a prospective study on a paediatric distraction technique. Emergency medicine journal. 2014; 31(4):327-8. PMID: 23629154

This is probably the most important article of the month. When you make a balloon out of a rubber glove for a child in the ED, which direction does the face go? Personally, I like the Mohawk technique, where the thumb is the nose (as should be clear from my title art for this post.) The other direction makes it look like the face has a weird tumor growing out of its neck. Who wants that? Well, now we have a scientific answer. The authors gave 149 children the option between the two types of balloon. The hand it was presented in was randomized to avoid natural left or right handed preference. 13 children refused to choose (it isn’t clear whether they wanted both, or just thought the doctor was a little bananas). Of the remaining children, there was really no difference. 55% liked the forward facing balloon, or what these authors call the Jedward technique, apparently for some pop singers I’ve never heard of. This wasn’t statistically significant, but I guess if we got a bigger trial it could be. I love the study, but I really dislike that the editors let them get away with concluding that the Jedward was better in a clearly negative trial.

Bottom line: Forget the science, I remain firmly against tumor neck.

A trial about distracted children and they didn’t even use a mobile phone

Inan G, Inal S. The Impact of 3 Different Distraction Techniques on the Pain and Anxiety Levels of Children During Venipuncture: A Clinical Trial. The Clinical journal of pain. 2019; 35(2):140-147. PMID: 30362982

This is another trial looking at distraction techniques for pediatric patients. This study actually took place on a phlebotomy unit. Basically, all children aged 6-10 who were undergoing phlebotomy were included. They were randomized to 4 different groups: playing a virtual reality video game (that could be played with one hand), watching a cartoon, parental interaction (such as storytelling, talking, or singing), or a control group with nothing. In the introduction, they talk a lot about the difference between active and passive distraction, so I am a little disappointed with the study design. You could have done a perfect active vs passive trial by just comparing virtual reality video games to virtual reality movies, but instead they complicate issues by making the passive and active techniques different. The kids got to choose among a few video games and cartoons, if they were in that group. I don’t know a bunch of the cartoon options – and that could make a big difference. If you are offering boring cartoons, your study failed from the outset. Overall, for both anxiety and pain scores, virtual reality was the best, and the control group was the worst. However, the confidence intervals are huge and overlap despite the p value of 0.001. Also, it isn’t clear to me whether a 2 point difference on this anxiety score is clinically significant.

Bottom line: I think distraction is important. Virtual reality is cool, and if designed well would make a lot of sense for this application, but I don’t think this study convincing enough to run out and invest in a system.

Choosing Wisely Hepatology (sounds exciting doesn’t it?)

Brahmania M, Renner EL, Coffin CS, et al. Choosing Wisely Canada-Top Five List in Hepatology: Official Position Statement of the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver (CASL) and Choosing Wisely Canada (CWC). Annals of hepatology. ; 18(1):165-171. PMID: 31113586 [free full text]

Just a quick, but clinically relevant update. This is a position statement from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign. There are two recommendations that we need to know in emergency medicine. 1) “Don’t order serum ammonia to diagnose or manage hepatic encephalopathy.” This was their highest ranked recommendation. They say the test is too inaccurate and does not add any diagnostic value. Hepatic encephalopathy is a clinical diagnosis, and should be confirmed by response to a trial of treatment. 2) “Don’t routinely transfuse fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K, or platelets to reverse abnormal tests of coagulation in patients with cirrhosis prior to abdominal paracentesis, endoscopic variceal band ligation, or any other minor invasive procedures.” These lab values don’t correlate well with bleeding risk in liver failure. Patients can have a high INR but still be hypercoagulable. It is reasonable to pay attention to extreme values (they say INRs over 2.5 and platelets below 20), but in general these values shouldn’t guide our decision to perform a procedure.

Cheesy Joke of the Month

What do you call an alligator wearing a vest?

Investigator

- Joke this month comes courtesy of Dr. Garreth Debiegun. (I am always happy to have cheesy jokes sent my way.)

Morgenstern, J. Research Roundup (November 2019), First10EM, November 18, 2019. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.9908

2 thoughts on “Research Roundup (November 2019)”

Thanks for this little update , its is appreciated

Re: “ Comparison of Wound Tape and Suture Wounds on Traumatic Wounds’ Scar”

I use more and more wound tape over time. I’d add a couple of tips. For many wounds, you can place multiple strips in nice alignment by pulling off the entire center paper section of the strips, while holding the small strips of paper on either end. Then you place all strips at once, leaving nicely spaced and nicely aligned strips. I agree with the crosshatching to secure the initial strips, but then I usually add a few more strips parallel to the first set, perpendicular to the second layer. Finally, I always send the patient home with extra strips with the instruction to “replace or bolster the existing strips for 8-10 days.”