Morgenstern, J. Overdiagnosis in the emergency department, First10EM, April 4, 2022. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.126031

Overdiagnosis is a concept that has long been part of my lexicon and is a driving force behind much of the philosophy on this website. However, I don’t think that I have ever formally discussed the topic. (Of course, if you have read my posts about cardiac stress testing, pediatric UTIs, or subarachnoid hemorrhage, you have read about overdiagnosis even if it remained unnamed.) It is a topic that might need a great deal more attention, but as a brief introduction for those unfamiliar with the term, there is a great paper that was just published by Marisa Vigna, Carina Vigna, and Eddy Lang.

The paper

Vigna M, Vigna C, Lang ES. Overdiagnosis in the emergency department: a sharper focus. Intern Emerg Med. 2022 Mar 5. doi: 10.1007/s11739-022-02952-8. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35249191

Summary

Overdiagnosis, by their definition, occurs when we turn “citizens into patients by the application of a diagnostic label that brings only harms and no benefits.” (Personally, I think this definition might be too strict. There are many times when the benefits of making a diagnosis are unknown or uncertain, which may effectively exclude them from this definition. Doctors will generally demand evidence for the claim that making a diagnosis has no benefit, while simply accepting that adding tests and medical labels is always beneficial. Furthermore, there are scenarios in which we know that there are benefits from making a diagnosis, but the benefits are very small and outweighed by known harms. That scenario doesn’t fit their definition, but still sounds like overdiagnosis to me.)

The essential basic concept is that sometimes (perhaps often) making a diagnosis can actually cause a patient harm. This might occur with incidental findings, when normal human variation is transformed into disease. It might occur with self resolving illnesses, such that a condition that would have disappeared on its own is medicalized, resulting in side effects from treatment but no chance of benefit. It might occur with very slowly progressive pathology which would have never caused the patient harm, but is now pursued with unnecessary interventions. False positives are technically a different concept, in that they represent an error with no true underlying pathology, but the result is the same: a patient receives an unnecessary or inappropriate label that ends up resulting in harm.

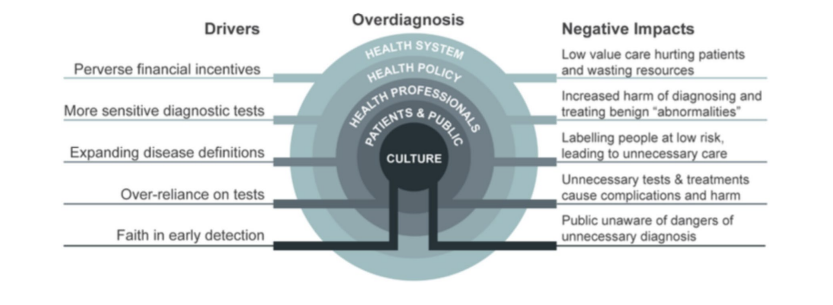

They discuss 5 key domains that drive overdiagnosis in medicine: pervasive financial incentives, increasingly sensitive diagnostic tests, expanding disease definitions, over-reliance on medical tests, and faith in early detection. The broad range of these drivers make overdiagnosis a difficult problem to solve at the bedside. Although physicians have a huge role to play in overdiagnosis, this is generally not a mistake being made by a single clinician. Overdiagnosis is the consequence of multiple aspects of modern healthcare, including medical education, funding models, research agendas, liability concerns, patient expectations, and physician expectations.

Over diagnosis is very easy to find in medicine. These authors provide us with 4 examples relevant to emergency medicine: subsegmental pulmonary embolism, aneurysms found in the workup of possible subarachnoid hemorrhage, low risk chest pain, and anaphylaxis.

Subsegmental pulmonary embolism is probably the most obvious example of possible overdiagnosis in emergency medicine. We have spent a lot of time talking about these PEs, and what we are supposed to do about them. We are never thrilled to make this diagnosis. It is unlikely that this tiny PE was actually the cause of the patient’s dyspnea, so it isn’t clear whether we should stop our workup (probably not). The PEs are so small, we wonder whether anticoagulation will help (probably not for most patients). The topic is complex, with a lot we don’t know, but there is definitive evidence that overdiagnosis is occurring. As the sensitivity of CT has improved over the decades, the prevalence of the diagnosis of PE has increased significantly, but there has been no change in patient important outcomes. In other words, all of these patients with extra PEs that we are finding used to do just fine when we were ‘missing’ the diagnosis. The anticoagulation we are prescribing can therefore only be causing harm.

I have written a little bit about the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. I think the evidence illustrates that there is very little role for lumbar puncture. However, because physicians are often uncomfortable with uncertainty, many have used the inaccuracy of lumbar puncture as an argument for broad use of CT angiogram. Unfortunately, because incidental aneurysms are common in the general population, most of which will never cause problems, and the ones we find often lead to invasive and potentially harmful procedures, the CT angiogram in the workup of headache is another potential example of harmful overdiagnosis.

Their next example of overdiagnosis is the use of stress testing in low risk chest pain. I actually think that most of the harm from stress testing is a result of false positives, but overdiagnosis is also definitively causing our patients harm. Stress tests inevitably lead to harmful, invasive procedures. However, we know that invasive management is net harmful in patients who aren’t having an acute MI. Therefore, every abnormal stress test that leads to an angiogram is an example of harm from overdiagnosis. (As a positive step forward, the AHA now specifically recommends against any further testing in low risk chest pain patients.)

Their final example, anaphylaxis, actually caught me off guard. I have thought and written about their other examples extensively, but anaphylaxis never really crossed my mind as an example of overdiagnosis. Their point is that there are a lot of patients with borderline symptoms, who probably never had a life-threatening allergic reaction, who we diagnose with anaphylaxis “just to be safe”. To be honest, I have probably been in this “better safe than sorry” camp when it comes to prescribing epi-pens. I am very aware of their cost, and often discuss finances with my patients, but if an insurance company is going to be paying for the Epi-pen, why not have one in the house? However, I will admit that I hadn’t fully thought through the downstream consequences of the labeling someone as anaphylactic. There may be extra ED visits, extra EMS usage, more expensive insurance, and the costs of medication if insurance changes or is lost. Perhaps more importantly, I may be causing significant quality of life issues if people are avoiding things they think they are anaphylactic to when they really aren’t. It turns out, anaphylaxis is a great example of overdiagnosis, and an excellent reminder that overdiagnosis probably plays a role in every single diagnosis we make in medicine.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this paper are the perspectives of two of the authors as medical students and patients. The medical student perspective highlights how the concept of overdiagnosis is essentially absent from formal medical education, and that learners are taught to be fearful of missing any diagnosis, with an educational culture that tends to drive more testing. The long term repercussions of our clinical decision making are rarely discussed outside of “bad misses” in morbidity and mortality type discussions. The solution is simple: this needs to be a core topic in medical education. No physician should practice without a clear understanding of overdiagnosis.

From a patient perspective, doctors first really need to understand these issues, and explain them to their patients. Patients need to be aware of the potential harms and long term consequences of receiving a diagnosis. Often, these harms can be avoided if the uncertainty in testing and diagnosis were discussed with the patient. Almost all of medicine’s problems can be solved by speaking with the most important person in the room – the patient – and truly embracing the ethos of shared decision making.

There are clearly many other perspectives we will need to consider if we are going to solve the problem of overdiagnosis, but this is a great start.

Bottom line

Overdiagnosis is a key concept that every physician needs to understand.

Other FOAMed

References

Vigna M, Vigna C, Lang ES. Overdiagnosis in the emergency department: a sharper focus. Intern Emerg Med. 2022 Mar 5. doi: 10.1007/s11739-022-02952-8. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35249191

8 thoughts on “Overdiagnosis in the emergency department”

Another great post – this is an escalating problem in our Emergency Medicine systems

“Unfortunately, because incidental angiograms are common in the general population…” Did you mean incidental subarachnoid hemorrhage here?

Also, in nursing school I was left with the impression that anaphylaxis would be a common occurrence. In 30 years I haven’t seen it once in any of my patients.

Yeah – now corrected type. Supposed to be “incidental aneurysms”

Thanks

Under diagnosis for anaphylaxis is another problem. I have mast cell activation syndrome and I have been in anaphylaxis several times and have been told that I was having a panic attack. No I was having a life threatening allergic reaction and wasn’t being listened to. So i don’t go to the emergency room anymore after using epinephrine injectors because it is useless. I have used over 75 injectors in the past three years. Messing with the smell of chemicals and other fragrances is more dangerous to my health.

article behind a paywall but I assume:

1. no mention of litigation

2. no mention of patient experience

3. no mention of over burdened health care systems and unsafe health care ratios

feels a lot like “tell me you don’t work in the ED without telling you don’t work in the ED”

No – I think those factors are mentioned, and are clearly drivers of overdiagnosis and the harm we do to patients.

Overinvestigation, overdiagnosis, overtreatment – the curse of modern medicine. Much of my clinical work is stopping unnecessary investigation or treatment of EM patients. We need to change our emphasis right from undergraduate level with a focus on “not doing stuff” rather than “doing stuff” and making sure that the stuff we do is needed and actually works. Kitchen sink by all means when required – masterful inaction much of the rest of the time.