Evidence based medicine is easy.

I know that evidence based medicine scares people. That stats seem complicated. Papers are often full of obtuse language. People are constantly debating small details at journal clubs, which can leave many physicians feeling inadequate.

But I can assure you, evidence based medicine is easy. If I can do it, anyone can. The only difficult part is getting into the habit of actually picking up a paper and starting to read.

I am a community emergency doctor with no special training in quantitative research methodology or epidemiology. Everything I learned about evidence based medicine I learned by picking up papers and reading them for myself (with some important insights from people like Jerry Hoffman and Rick Bukata on the Emergency Medical Abstracts). This post runs through the simplified approach I take when reading the medical literature, with the hope that I can convince you that you are also capable of taking an active role in critiquing the medical literature.

Step 1: How do I find a paper to read?

When you are just starting out, I would suggest picking a paper that other people are also reviewing. This could be a paper that was chosen for your group’s journal club, that was featured on a program like the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine, or one that you found in my Articles of the Month. Read the paper yourself, write down your conclusions, and then compare your thoughts to the conclusions of other experts who have read the same paper.

Eventually, you will probably find it limiting to only read papers chosen by others. Having access to a list of newly published research allows you to pick the topics that are most interesting to you. I currently get all of the abstracts from 47 different journals, but that is simply way too much for most people. Just pick one or two high impact journals in your field to scan each month. You can opt to receive notifications of new publications by e-mail, or you can subscribe to the journal’s RSS feed.

If you are interested in a specific topic, another great option is to set up a pubmed email alert. It does require that you create a (free) NCBI account, but is easy and ensures that you will never miss an important paper on a topic that interests you (such as “sexual intercourse for the treatment of nephrolithiasis”).

Step 2: Is this paper worth reading?

I use the title and abstract to decide whether a paper is worth reading. However, to save time, I don’t read the entire abstract. First, I skip directly to the conclusions. If a paper’s conclusions are not interesting, or don’t seem relevant to my practice or my patients, I can throw the paper away and not waste any more time. If the conclusions seem interesting, I will look at the methods described in the abstract. If the methods are clearly poor or irrelevant to my current clinical practice (such as animal studies), I will not read the paper. If the conclusions are interesting and the methods seem reasonable I will download the paper to read.

Step 3: Read the paper

At first glance, papers seem long and dense. They are intimidating. simply scanning through a 16-page pdf is often enough to kill one’s desire to read. Luckily, many of those pages are superfluous. Most of the time, we can be much more efficient in our reading if we understand the structure of a paper:

Title: Helpful (sometimes) for finding the paper in your original search, but basically useless after that.

Abstract: This quick summary of the paper helps you decide if a paper is worth your while. However, the details are far too scant to help us make clinical decisions, so we can skip the abstract when we actually sit down to read a paper.

Introduction: This section provides background information on the topic. However, the data presented is not the result of a systematic review. There is a lot of room for bias in the introduction section. In a lot of ways, the introduction section is just a summary of the authors’ opinions on the topic. If the topic is completely new to you, you might find this background information helpful. Most of the time, though, I just skip the introduction section.

Methods: This is the most important part of any research paper. Good results are meaningless without high quality research methods. Expect to spend most of your time here. The methods section is often the most confusing section, with esoteric language or jargon, but a simplified approach is possible. I will get back to that in a minute. If the methods are very poor, you can save yourself time by stopping now, because with poor methodology you are unlikely to be convinced to change your practice, no matter what you find in the following results section.

Results: This is the real reason you picked up the paper in the first place. You want to know what the study showed, so you are going to have to read through the results section. There are often many different results presented. If you are feeling overwhelmed, focus on the primary outcome of the study (which should have been clearly stated in the methods section).

Discussion: This is another non-systematic review the literature. The authors compare their results to prior studies. Like this introduction, this section represents the opinions of the authors’. Usually, I skip the discussion section.

Conclusion: This is the author’s opinion of what their results show. At this point you have already read the methods and results and so should have already drawn your own conclusions about the paper. You don’t need to read the authors’ conclusions unless you want a taste of the subjectivity present in scientific publication.

Therefore, although papers often seem overwhelming long, we can cut down on the amount of time we spend reading by sticking to the most important sections. All of the study’s objective science is found in the methods and results sections. The remaining sections add the authors’ subjective interpretations, which can be safely skipped most of the time.

Apparently I am not the only one who skips large chunks of research papers. A very similar approach to reading papers is outlined on Sketchy EBM:

Step 4: Interpret the paper (stats are less important than you think)

Medical research can certainly get very complex. Papers often include language understandable only if you have a PhD in statistics. However, the vast majority of the time a quality critical appraisal is possible by simply asking a few common sense questions as you read.

You can think of a trial like a race. We want the race to be fair. In order to be fair, the race has to have a fair start (all patients start the trial at the same spot), everyone needs to run the same course (all trial participants are treated similarly except for the intervention), and there needs to be a fair finish (the outcome is measured the same for everyone, without bias).

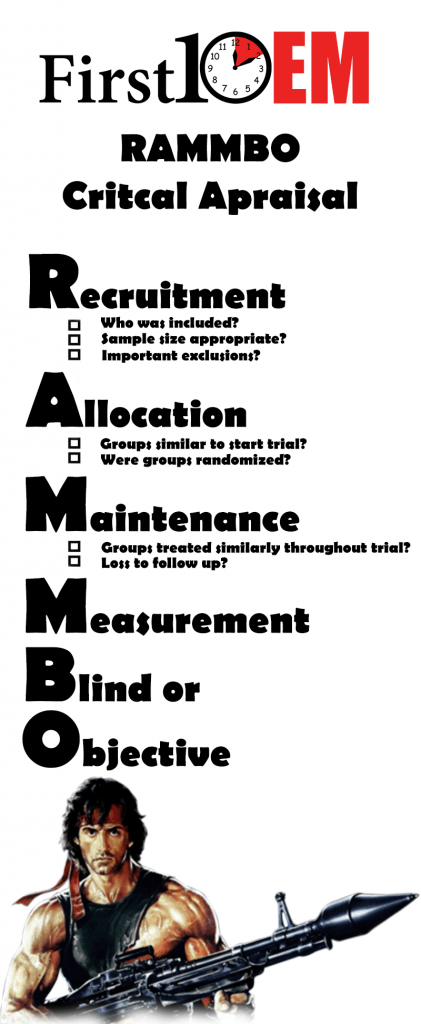

One framework I keep in mind when reading papers is the RAMMBO approach:

- Recruitment

- Allocation

- Maintenance

- Measurement: Blind or Objective

Recruitment

- Who was included in this study? Do the study patients look like my patients?

- Is the study size appropriate? (Ideally, this should be easy to tell, because the researchers will describe their sample size calculation).

- Were there important exclusions that could affect the results?

Allocation

- Were the groups similar at the beginning of the trial?

- Was assignment to treatment groups randomized? If assignment wasn’t randomized, it is worth considering what factors might have made the groups systematically different (confounders), but keep in mind that it is not possible to identify all confounders.

Maintenance

- Were the groups treated similarly throughout the trial (aside from the intervention of interest)?

- Were the outcomes of interest measured for all (or at least most) of the patients in the trial? (In other words, were patients lost to follow up, which could affect the reliability of the results?)

Measurement

- Were patients, clinicians and researchers all blinded to the treatment? (Bias is much more likely when people are aware of the groups patients were assigned to).

- Or, were the outcomes objective and standardized? (In an unblinded trial, bias is less likely with an objective outcome like mortality than it is with a subjective outcome like satisfaction with treatment).

- Are they measuring something that I or my patients really care about? (Was this a patient oriented outcome?)

- Were harms adequately measured?

These simplified RAMMBO questions help me distill the methods section down into common sense questions that I can understand. They are primarily aimed at assessing the validity of the trial’s results. After I finish reading a paper, I like to pause and ask myself a few other questions to help place the trial in its appropriate context:

- Why was the study done?

- Is the question important?

- Does anyone have a vested interest in the outcome?

- Is the benefit big enough?

- To answer this question, you have to consider both how the benefits weighs against harms, but also the cost that any new intervention might have.

- How does this study fit with previous research?

In my opinion, the answers to these questions are far more important than any of the statistics or p values you might struggle with while reading. I always consider these questions before I even look at the statistics presented. Although comfort with critical appraisal does require some practice, these questions are relatively straightforward and, I think, make basic critical appraisal easy for any practicing clinician.

Step 4: Use a checklist

Most of the time, the basic questions above are all you need when appraising an article. However, sometimes if a paper is more complex or if I am tackling a more important question, I want to be more thorough with my critical appraisal. In those situations, I recommend using a checklist to help assess all the possible sources of bias in a paper. There are many checklists available. I generally use the Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine (BEEM) checklists:

- Randomized Clinical Trials

- Systematic Reviews

- Diagnostic Studies

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Clinical Decision Instruments

- Prognostic Studies

More checklists and EBM tools can be found here.

Step 5: Ask for help

Although I think evidence based medicine is easy, I will admit that there are some aspects that can get very complex. As practicing physicians, it doesn’t make a lot of sense for us to learn everything about epidemiology. We need to be expert clinicians, not statisticians. The solution is simple: know when to ask for help.

Start by reading the paper, but when you come across topics that you don’t fully understand, reach out for some help. There are many incredible resources when it comes to evidence based medicine. Obviously, we have the #FOAMed community, with many excellent podcasts and blogs that can help with critical appraisal. I plan on updating this blog with a number of EBM resources in the coming year, so keep an eye on https://first10em.com/EBM for added resources. Reaching out to experts directly can also be helpful. As I struggled to learn critical appraisal, I have emailed experts like Jerry Hoffman, Ken Milne, and Andrew Worster on multiple occasions, and each time have been rewarded with friendly and brilliant responses. Local experts like medical librarians and university research methodologists are also excellent resources. Finally, don’t underestimate the value of a simple search on google or youtube.

Step 6: Apply the research

This is where evidence based medicine can get complex. Reading and appraising papers is easy, but real evidence based medicine requires that clinicians interpret the evidence through a lens of clinical expertise and with patient values in mind. Evidence based medicine is not just about the literature. “Evidence-based medicine is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” (Sackett 2000)

This is why you are already an evidence based medicine expert. This is why it is better for practicing clinicians to read the literature than expert methodologists. Although a statistician will have incredible insight into the mathematics of the paper, it is only the practicing clinician who can adequately filter the information through their clinical expertise, explain it in simple terms to their patients, and make decisions that mesh the best available evidence with the values of the patient. That is evidence based medicine. These discussions (which we all have every shift) are complex. In comparison, reading the literature is simple, so why not give it a try?

References

Sackett D et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd edition. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2000, p.1

Morgenstern, J. Evidence Based Medicine is Easy, First10EM, January 8, 2018. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.51684/FIRS.5554

Thank you to Dr. Ken Milne and Dr. Andrew Worster for providing feedback on this blog post.

10 thoughts on “Evidence Based Medicine is Easy”

EBM is easy, EMDocs

Hi Justin, great post! I would have saved enormous time if I’d read it 10 years ago!

I believe we could add some simple tips to fully appreciate the clinical usefulness of a paper.

1. Evaluate inclusion & exclusion criteria of the studied population. This gives you an idea of the generalisability of the results, since you can easily compare the cases you see in your clinical practice with patients enrolled in the RCT.

2. P value is not a mantra nor magic, rather a statistical convenience that has to pass the clinical significance. See the fantastic video/post from Lauren Westafer (goo.gl/QSVpqu)

3. For RCT on treatment, use the NNT, that gives you a definite idea of the clinical impact of the effect of an intervention (see the wonderful thennt.com for details and explanations)

4. The fragility index (goo.gl/PAfzVN). The is another useful tool to further define the robustness of statistical significance. According to the authors, the fragility index is a number indicating how many patients would be required to convert a trial from being statistically significant to not significant (p ≥ 0.05). The lower the value, the more fragile the significance (and viceversa).

Thanks for the comment Roberto!

This post was meant to be introductory, and the plan is to address more critical appraisal issues over time at https://first10em.com/ebm/

There is already a short post on the fragility index, links to a bunch of calculators, and a post on understanding the p value (and yes, Lauren Westafer’s video is included), as well as a bunch more content, should be coming soon.

Evidence-based medicine is about making use of the best available information to answer questions in clinical practice. Evidence based medicine, at its very core, requires the assessment of evidence by experienced clinicians in the context of real patients.

Thank you very much.

Your article is very useful